Fast on-the-Wire Formats

Visual guide to memory representation of on-the-wire formats

Serialization is an evolving space. Every few months we see new formats, on-the-wire optimizations popping up that claim to be better than the other.

Let’s first address the elephant in the room -

When do you need serialisation?

It’s the time when objects cross boundaries. Imagine a server sending a batch of records to remote workers for processing.

But, why?

The way an object is represented in memory is vastly different not just across languages but different systems of same language (because of the things like endianness).

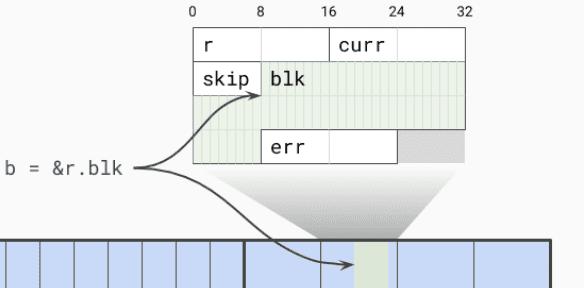

For example, this is a logical view of go struct. (Note - blk is pointer to another address)

It is not difficult to imagine a different layout in java script or even across different versions of go. For this reason, when we transfer data from objects across system we tend to bring the source data in a common format that is understood by the other side.

The downside of this, we always need to map the wire format back to an object in target language.

JSON is most common format that web applications tend to use. While it is are widely used, its not the most efficient one. So in this article, I want to mainly look at protobuf and flatbuf.

Protobuf

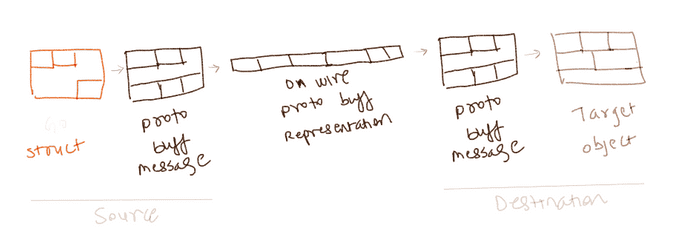

Unlike JSON, the protobuf requires a schema definition. This helps it map data /variables into a fixed format and send over the wire

In the image above, protobuf message and the encoded data on the wire are in different format. This allows protobuf to offer more flexibility across versions. But it also incurs additional cost of serialisation.

Flatbuf

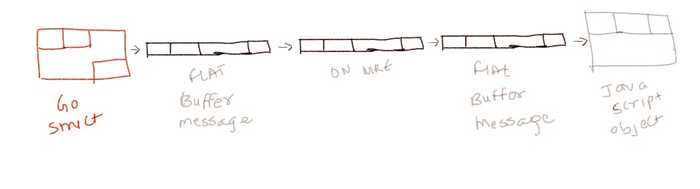

To optimise protobuf further, the flatbuf writes the message (in memory) in the same format as what will go through the wire. This makes flatbuf more efficient for RPC that its cousin protobuf.

Trade off

Flatbuf design optimises memory footprint but looking at design they don’t seem to be backward compatible. For example, if INT16 was mapped to 4 bytes (INT32) and a new version (of flat buff) changes that to 8 bytes then the source and destinations will need have same version of flat buff. These changes are seem unlikely though.

On the other hand, protobuf looks more stable across versions.

RPC Bottleneck

Finally, the optimised memory representation on the wire looses its significance due to the way most RPC systems are built. Most network libraries like RPC, tornado IO were originally designed to serve web frontends. All of them break down the buffer into smaller pieces which makes them slower for massive data transfers.

Dask developer log has a good write up on this problem. I am seeing the same issue popup in Arrow community discussions. Even for Spark jobs the shuffle operations are their achelis heel as they require transfers between workers.

Apache plasma aims to solve this by creating a shared object pool.

More I come across this, the more I sense a growing need a data RPC mechanism thats built from ground up for large data /array transfers between worker-server or worker-worker(s).

Image credit: Go struct